By Hannah Budnitz and Emmanouil Tranos

When COVID saw the UK government tell people to work from home in early 2020, the expectation was that they would use digital technologies to do so. Scientists worldwide have since highlighted how the pandemic has intensified the effect of the digital divide (the gap between those who have access to the latest technology and those who do not).

Amid its COVID recovery plans for England, the UK government is aiming to expand digital infrastructure, 5G and fibre optic broadband across the country.

As our research shows, however, bridging the digital divide is about more than making sure everyone has access to digital infrastructure and having the skills to use it. Communication scientists speak of the third level of the digital divide: the capacity to use digital technologies to enhance economic activities.

Patterns of demand

Household demand for bandwidth to download large video files or stream faster from online television services has been growing for a long time. Conversely, until the pandemic hit, relatively few people were using data at a volume that would have affected network performance.

When half the workforce started working from home, however, and the country’s schoolchildren and students were sent home too, videoconferencing took off. We expected this extreme demand for telecommuting during working hours to change the pattern of internet use and broadband performance.

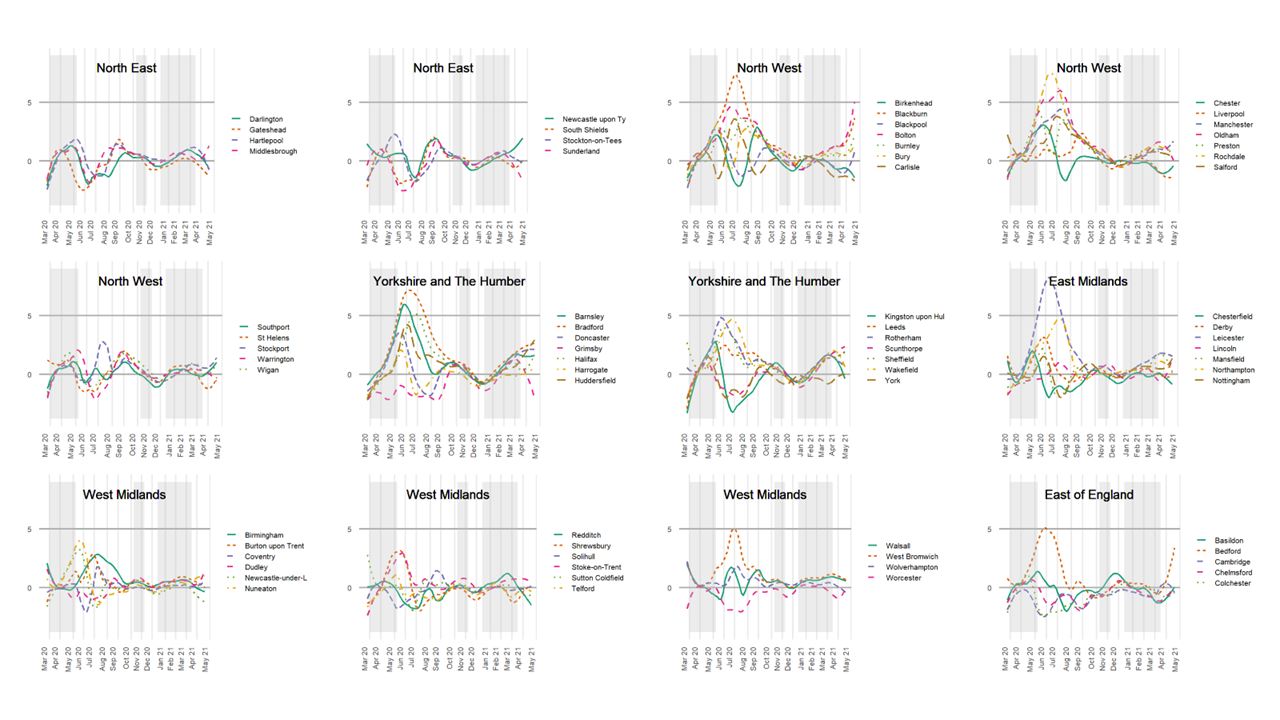

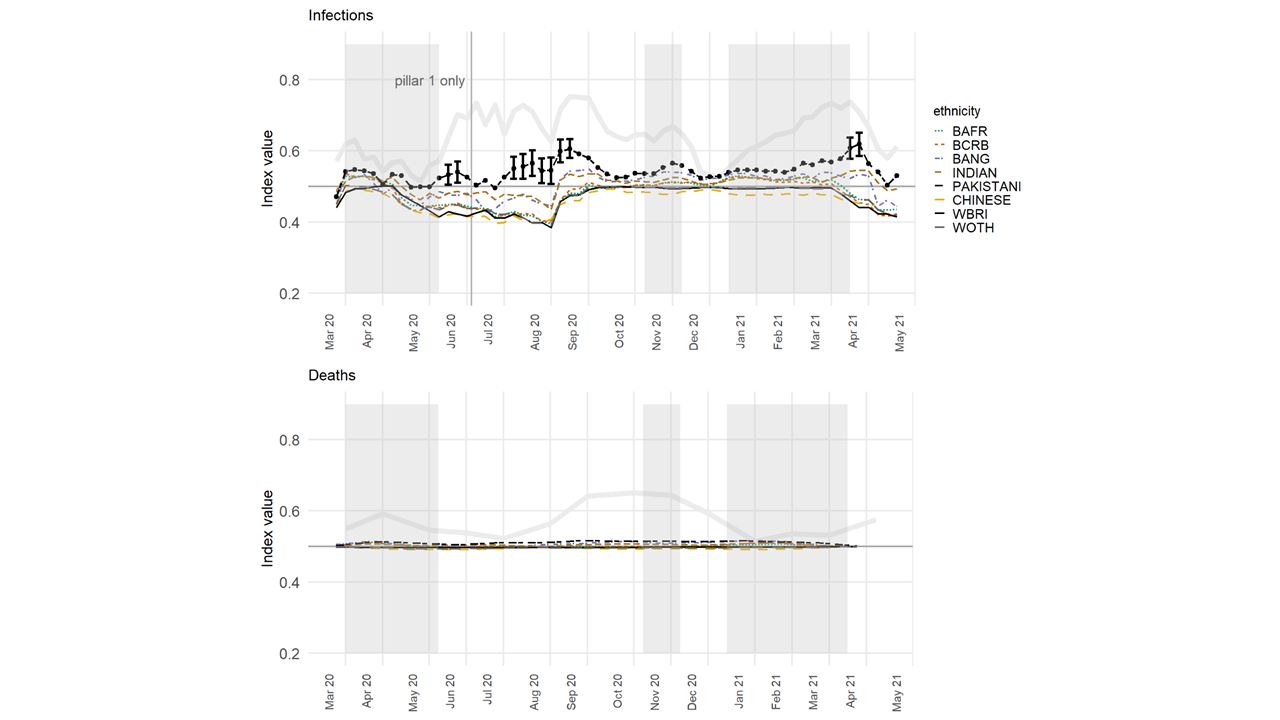

To determine how this affected the economic resilience of different places — their capacity to maintain economic activity — during the pandemic, we analysed data on the upload and download speeds that internet users experienced during the first UK lockdown in 2020.

We found that patterns of demand changed a lot in most of the UK, both in terms of download and upload speeds. People weren’t only using the internet to download data (movies or music, for example) but to upload data, primarily for videoconferencing. Zoom, after all, counted 300 million daily meeting participants worldwide at its April 2020 peak.

Socio-economic correlations

Now, only half of the UK’s workforce were able to continue working remotely. The other half still had to go into work or were furloughed.

To understand whether existing economic divides and digital divides overlapped or diverged, we first created clusters of local authorities based on upload internet speeds as experienced by internet users in these places during the lockdown. We then correlated these clusters with various economic and geographical variables: distances to cities, the north-south economic divide, different occupations, average earnings, number of jobs and businesses, and furlough numbers.

Our findings indicate that areas, including Bristol and Cambridge, with relatively slow and unreliable internet services were not those with the highest percentages of people on furlough. Increased demand for digital services such as Zoom and the resulting network congestion occurred in these areas where (and perhaps because) occupations were more economically resilient: they were able to continue operating despite the pandemic.

Conversely, some areas with reliably high broadband speeds, suffered economically as reflected in high furlough numbers. These areas are characterised by a lack of jobs in the kind of occupations (technology and business services) that enable workers to be productive at home.

The temporary shift to flexible working models ushered in by the pandemic appears to be lasting. Some employers want their staff to return to the office, but many more are planning for hybrid or flexible working. A few are considering a permanent shift to remote working.

This means that the demand for fast and reliable upload and download speeds during working hours in residential areas is here to stay. Ofcom’s latest reports already include more data on upload speeds, and internet service providers will no doubt need to focus more on what customers need during working hours. Government ministers, meanwhile, should be thinking not only about 5G and the wider digital infrastructure, but also about the sort of jobs and skills people need in order to make the best use of it.

As our research illustrates, in order for a place to be economically resilient — for the local economy to continue to operate — during a pandemic, government ministers, community leaders and economists alike need to consider not only the digital divides linked to the internet’s physical infrastructure, but also the associated economic and social divides.

Broadband policies, although necessary, cannot boost the economic resilience of places on their own, where the industrial structure does not align with occupations that incorporate the digital skills and capabilities to work from home. This complex web of digital and socio-economic divides needs to be incorporated into our thinking of local economies and government priorities.